Unless otherwise noted, all images provided by the Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Occupied Williamsburg

Although the main Federal army passed through Williamsburg in the days immediately following the battle just outside of town, the city remained occupied and came under martial law, a military form of government under which private citizens have very few individual rights. Williamsburg would soon have the dubious distinction of being the "border" between the United States and the Confederacy on the Peninsula. Over the next three years, Williamsburg would endure the most challenging period of its history. The town's inhabitants labored under what they considered a "foreign" occupation. Federal troops, in turn, struggled with resistant townspeople, Confederate guerilla raids, and the slavery question.

“The repudiated Stars and Stripes are now waving over our Town, and humiliated I feel, we bow our heads to Yankee despotism.”

Polite Resistance

With the departure of the Confederate army, the town now consisted of mostly old men, women, and children. The women were especially loyal to the Confederacy and went out of their way to make life difficult for the occupying Federal troops. Captain Henry Blake of the 11th Massachusetts Infantry noted that the women "compressed their dresses whenever they met an officer or enlisted man, so that the garments would not touch the persons they pass-ed. They pulled their hats over their faces to preclude scrutiny." On Main

Street, the ladies deliberately walked in the street rather than under the U.S. flag hung over the sidewalk at Mr. Harrell's Lodging House, now the Federal Commissary. The Union soldiers responded by stretching a long flag across Main Street so that the "secesh" had to walk under it. Some-times, though, the resistance was less polite. While assisting the wounded, Delia Bucktrout only agreed to provide water to a Union soldier because he was injured. She stated clearly that she would otherwise have killed him!

View looking east on Main Street of the 1770 Courthouse and Spencer Hotel (Mr. Harrell's Lodging House in 1860), ca. 1890s

Confederate Raids

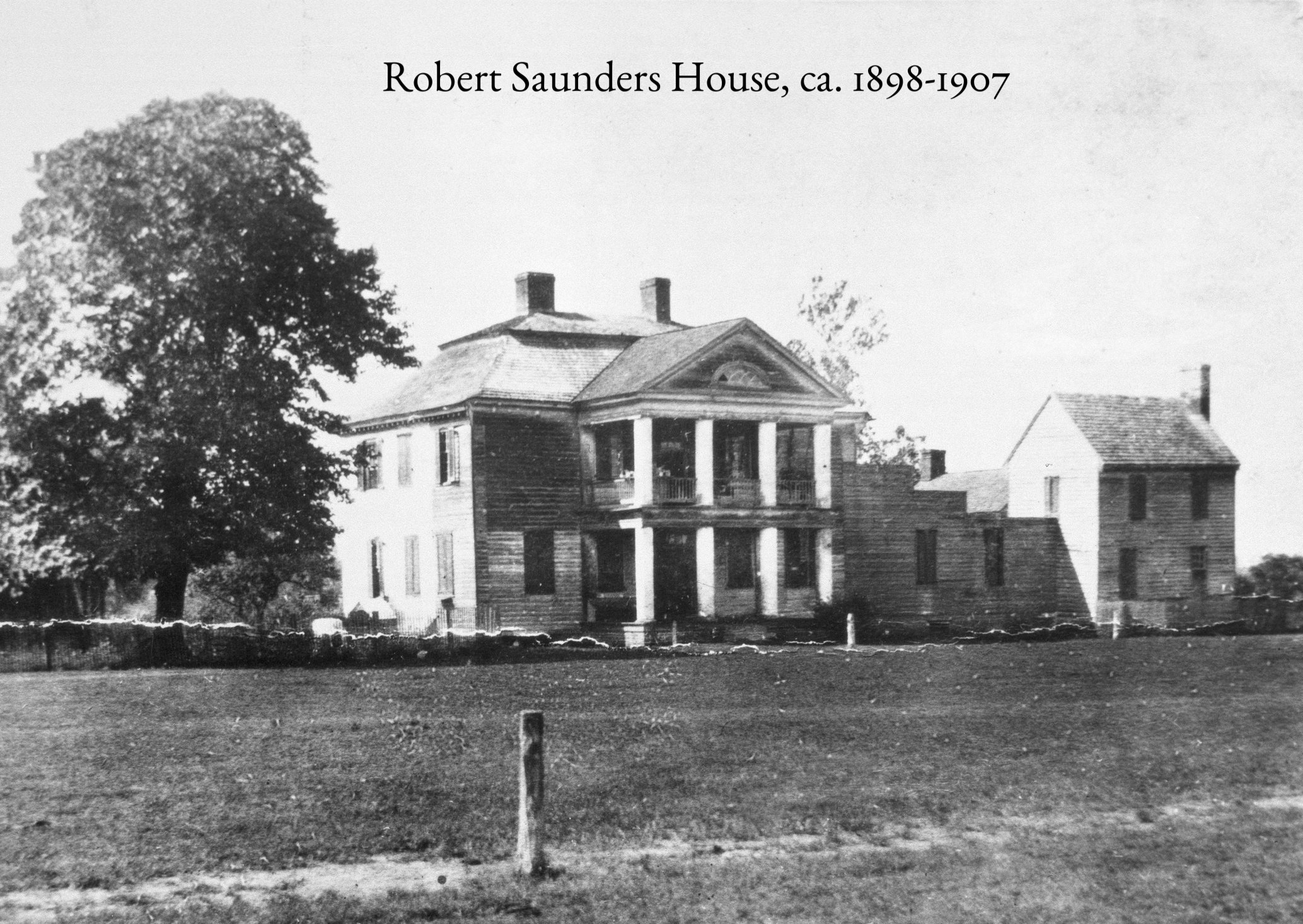

Confederate raiders were a constant threat to Federal pickets and patrols. The town was the scene of several skirmishes and even occasional street fighting. In September 1862, Confederate raiders swept in from west of the College of William and Mary and captured the provost marshal (military governor) asleep in his bed at the Robert Saunders (present Robert Carter) House on the Palace Green. Later that same day, embarrassed, outraged (and drunk) soldiers of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry burned the Wren Building in retaliation and threatened harm to any citizens who tried to douse the flames. The new provost marshal also moved his headquarters to the Vest Mansion (now Palmer House) at the far east end of town.

In February 1863, the Federal provost marshal closed Bruton Parish Church because the rector there, Rev. Thomas M. Ambler, refused to pray for the president of the United States. Perhaps in retaliation for the closure, Confederates attempted to retake Fort Magruder early on March 29. The plan was aborted at the last moment, and the raiders tried retreating west along Main Street. They found their path blocked by Union cavalry but fought their way free, leaving a haze of smoke and several dead and wounded Federals. Two weeks later on April 11, Confederate raiders struck again. This time, the Union soldiers withdrew to Fort Magruder and shelled the town. Resident John Coupland described the frightful ordeal, writing that "houses were struck and portions of them torn to pieces." He and others took their families to the Lunatic Asylum for protection or camped in the woods. Miss Sally Galt wrote that "Col. Durfeys family have been staying with us for several days, as their yard ... is the skirmishing ground & rifle balls are perforating the house a dozen times a day ..." After occupying the town for a week, the Confederate force withdrew accompanied by many Williamsburg residents. Federal soldiers re-entered the town, and life for the remaining citizens became even tougher.

Lithograph of the Lunatic Asylum, ca. 1845

Col. Goodrich Durfey's home (present Bassett Hall), ca. 1928

The Market Line

As a result of these raids, Federal auth-orities closed the town's stores and would only issue rations to citizens who swore the oath of allegiance to the United States. Citizens also could not leave town or, for those who had pre-viously departed, re-enter without tak-ing the oath. Most residents refused, and feeding the population soon be-came a matter of concern. To alleviate the situation, the provost marshal established the "Market Line." Each week on "Line Day", two parallel wires were stretched across Stage Road just west of the college, and farmers from Confederate held territory could bring their produce to the wires to trade with

the town's inhabitants. Sentries patrolled between the wires, but news-papers, personal and diplomatic letters, and other prohibited articles still passed back and forth hidden in bonnets, hoop skirts, stuffed poultry, jelly jars, and plugged melons. The Market Line also served as a meeting place for family and friends separated by the divide between Union and Confederate controlled ground. Mrs. Cynthia Coleman, who had slipped out of town in 1862, spent a snowy December night in 1864 at the line with her mother, sitting by a fire under an umbrella eating cake and drinking toasts before the watchful, but sympathetic, eye of a guard.

St. George-Tucker House, ca. 1904 (home of Mrs. Cynthia Bevery Tucker Coleman)

Slavery & Emancipation

With the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Will-iamsburg faced a difficult interpreta-tion. The proclamation freed slaves only in those areas of the Confederacy still in rebellion. Half of the city was in James City County, which was under Confederate control, and the other half in York County, which was under Fed-eral control and, therefore, specifically excluded from the proclamation. The provost marshal resolved the situation by declaring that all slaves in Williams-burg proper were free. Thus slavery ceased to exist in the town. A few form-er slaves remained loyal to past masters

while others hired themselves out or departed for new opportunities. Three African-American residents of the town are known to have spied for the Con-federacy during the occupation. Others joined the United States Army to fight against their former masters, and at least two regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT) were quartered near the town in 1864. Towards the end of the war, African-American children were being educated in the basement of the Williamsburg Baptist Church, and the Freedmen’s Bureau arrived in 1865 to assist former slaves in adjusting to a free society.

View from south of the ruins of the Palace West Advance with George Wythe House and Bruton Parish Church in left background and Robert Saunders House in right background, ca. 1900

Reconstruction

The last military action around the city occurred on February 11, 1865 as Con-federate cavalry swept into the eastern part of the town. After causing much early morning confusion, the raiders quickly withdrew. With the surrender of Confed-erate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, VA in April 1865, an uneasy but welcome piece returned to Virginia and Williamsburg. The city continued to be occupied, and Virginia became Federal Military District Number One in the Re-construction Period. Stores and churches reopened, and movement restrictions were lifted. Ex-Confederate soldiers and refugee residents returned to begin their lives anew. Some stayed, but others lost heart and left for good when they found their former homes and businesses destroyed. Federal troops remained in the city proper until September 1865 and in the surrounding counties until 1870. With their with-drawal, one of the darkest periods of the town's existence slowly began to fade into the past. Williamsburg would not fully recover until the 20th century.